The First Triumvirate and Civil War

The alliance that formed between three individually powerful men of Rome was tenuous at best and borderline illegal at worst. In part one we talked about increasingly powerful generals, leading armies that were loyal to the commander they had served with for years. In this part, we will see perhaps the two greatest generals at odds with each other.

If you’re a fan of the Hunger Games series, you might have some idea of what this alliance will turn out like. The three tributes may work together as long as they see personal benefit, but only one will be crowned victor. Once the balance of power shifts, alliances are broken. In this arena of eastern and western provinces, Rome is the cornucopia each man strives for.

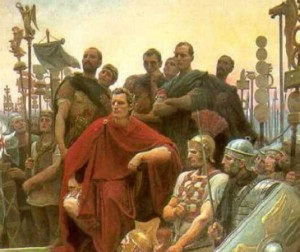

The First Triumvirate was made up of Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus. After this we’ll shorten the names to Crassus and Pompey. Within the alliance Crassus and Pompey were the more senior members. Crassus was enormously wealthy, perhaps the wealthiest man in Roman history, and Pompey was a celebrated military leader of several victorious campaigns. Julius Caesar, though younger, was a popular up-and-coming politician with charm and promise. Together, the Triumvirate was able to politically out-manuever the opposing political party, the Optimates, led by Cicero and Cato the Younger.

The First Triumvirate was made up of Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus. After this we’ll shorten the names to Crassus and Pompey. Within the alliance Crassus and Pompey were the more senior members. Crassus was enormously wealthy, perhaps the wealthiest man in Roman history, and Pompey was a celebrated military leader of several victorious campaigns. Julius Caesar, though younger, was a popular up-and-coming politician with charm and promise. Together, the Triumvirate was able to politically out-manuever the opposing political party, the Optimates, led by Cicero and Cato the Younger.

While the situation was detrimental to the Republic’s integrity, the members of the Triumvirate had successfully taken power. With the support of Crassus and Pompey, Julius Caesar was elected consul, then proconsul in 58 BCE, making him governor of provinces. Caesar’s land reforms were pushed through with the help of his allies and he left Rome to pursue a successful campaign known as the Gallic Wars. But in 53 BCE, Crassus sought his own military victory against the Parthians, was defeated and murdered. His death tipped the scales of power and set Caesar and Pompey at odds against each other. The death of Pompey’s wife Julia, who was also Caesar’s daughter, severed the last link between the two men. Distrust, suspicion and ambition drove the two men apart.

With Caesar pursuing victory after victory in Gaul, his loot was able to fund his generosity and win him loyal allies. He doubled the pay of his troops and called in more legions to reinforce him from Gaul. But in 51 BCE, a motion was put before the Senate to order Julius Caesar to give up his command at the end of his term and return to Rome. Caesar counter-offered, and declared he would give up his command if Pompey was ordered to do the same. The Senate threw their support behind Pompey and granted him funds and troops should Caesar become a greater threat. In January of 49 BCE, Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, the border of the province of Cisalpine Gaul and Roman territory, with his 13th Legion. To enter Rome with an army was considered a strike against the Republic and it is said Caesar uttered the phrase “Alea iacta est” meaning “The die is cast” as he did so.

In the absence and growing mistrust of Caesar, the Senate had appointed Pompey as sole consul, effectively kicking Caesar out of the club. When Caesar marched toward Rome, Pompey declared Rome indefensible and fled to Brundisium, then across to Greece. Once Caesar had secured his position in Rome he pursued Pompey across Greece where the final battle took place at Pharsalus in 48 BCE. Julius Caesar defeated the army of Pompey, who escaped and sought asylum in Egypt, but was murdered as soon as he stepped off of his ship. The last supporters of Pompey were finally defeated in Spain, at the Battle of Munda in 45 BCE.

After the battle of Pharsalus, Caesar set out for Pompey anticipating that he would seek funds and support from Ptolemy XIII, the young king of Egypt. He arrived too late as we know, but resolved a dispute over who would rule Egypt, a very young Ptolemy XIII or his elder sister Cleopatra VII. After a siege, reinforcements arriving, and consequently being locked in the palace while this all happened, Caesar’s forces captured the port and Cleopatra emerged as ruler as well as pregnant with a child who would be called Caesarion.

When Julius Caesar returned to Rome, he did so as an emperor in all but title. His military victories had made him the master of the Roman world. He was generous in forgiving old grievances and instead of a widespread massacre of old enemies, he sought amnesty instead. He initiated many reforms both on economic policy as well as political. He expanded the senate, took a census, planned the Forum of Caesar, and created the Julian calendar. But just because Caesar was the first to forgive, doesn’t mean his contemporaries would extend the same courtesy. In the wake of Caesar’s many changes opposition remained wary of Caesar’s concentration of power. In an end made famous by William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar ignored the advice of the soothsayer and went to the Senate on the ides of March 44 BCE, where he was assassinated by a mob led by Marcus Junius Brutus. The conspirators meant to save the Republic perhaps they only proved that city needed a single manager over the factions that vied for Rome.